|

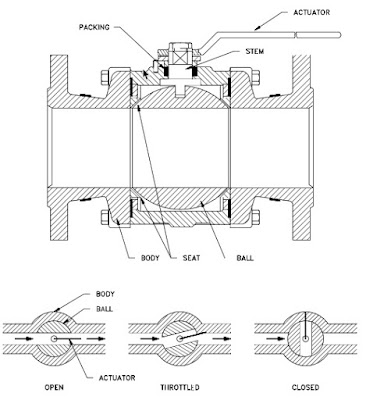

| Fig. 1 - Parts of a valve. |

A valve is a mechanical device that controls the flow of fluid and pressure within a system or process. A valve controls system or process fluid flow and pressure by performing any of the following functions: 1) Stopping and starting fluid flow; 2) varying (throttling) the amount of fluid flow; 3) controlling the direction of fluid flow; 4) regulating downstream system or process pressure; 5) relieving component or piping over pressure.

There are many valve designs and types that satisfy one or more of the functions identified above. A multitude of valve types and designs safely accommodate a wide variety of industrial applications.

Regardless of type, all valves have the following basic parts: the body, bonnet, trim (internal elements), actuator, and packing. The basic parts of a valve are illustrated in Figure 1.

Valve Body

The body, sometimes called the shell, is the primary pressure boundary of a valve. It serves as the principal element of a valve assembly because it is the framework that holds everything together.

The body, the first pressure boundary of a valve, resists fluid pressure loads from connecting piping. It receives inlet and outlet piping through threaded, bolted, or welded joints.

Valve bodies are cast or forged into a variety of shapes. Although a sphere or a cylinder would theoretically be the most economical shape to resist fluid pressure when a valve is open, there are many other considerations. For example, many valves require a partition across the valve body to support the seat opening, which is the throttling orifice. With the valve closed, loading on the body is difficult to determine. The valve end connections also distort loads on a simple sphere and more complicated shapes. Ease of manufacture, assembly, and costs are additional important considerations. Hence, the basic form of a valve body typically is not spherical, but ranges from simple block shapes to highly complex shapes in which the bonnet, a removable piece to make assembly possible, forms part of the pressure- resisting body.

Narrowing of the fluid passage (venturi effect) is also a common method for reducing the overall size and cost of a valve. In other instances, large ends are added to the valve for connection into a larger line.

Valve Bonnet

The cover for the opening in the valve body is the bonnet. In some designs, the body itself is split into two sections that bolt together. Like valve bodies, bonnets vary in design. Some bonnets function simply as valve covers, while others support valve internals and accessories such as the stem, disk, and actuator.

The bonnet is the second principal pressure boundary of a valve. It is cast or forged of the same material as the body and is connected to the body by a threaded, bolted, or welded joint. In all cases, the attachment of the bonnet to the body is considered a pressure boundary. This means that the weld joint or bolts that connect the bonnet to the body are pressure-retaining parts.

Valve bonnets, although a necessity for most valves, represent a cause for concern. Bonnets can complicate the manufacture of valves, increase valve size, represent a significant cost portion of valve cost, and are a source for potential leakage.

Valve Trim

The internal elements of a valve are collectively referred to as a valve's trim. The trim typically includes a disk, seat, stem, and sleeves needed to guide the stem. A valve's performance is determined by the disk and seat interface and the relation of the disk position to the seat.

Because of the trim, basic motions and flow control are possible. In rotational motion trim designs, the disk slides closely past the seat to produce a change in flow opening. In linear motion trim designs, the disk lifts perpendicularly away from the seat so that an annular orifice appears.

Disk and Seat

For a valve having a bonnet, the disk is the third primary principal pressure boundary. The disk provides the capability for permitting and prohibiting fluid flow. With the disk closed, full system pressure is applied across the disk if the outlet side is depressurized. For this reason, the disk is a pressure-retaining part. Disks are typically forged and, in some designs, hard-surfaced to provide good wear characteristics. A fine surface finish of the seating area of a disk is necessary for good sealing when the valve is closed. Most valves are named, in part, according to the design of their disks.

The seat or seal rings provide the seating surface for the disk. In some designs, the body is machined to serve as the seating surface and seal rings are not used. In other designs, forged seal rings are threaded or welded to the body to provide the seating surface. To improve the wear-resistance of the seal rings, the surface is often hard-faced by welding and then machining the contact surface of the seal ring. A fine surface finish of the seating area is necessary for good sealing when the valve is closed. Seal rings are not usually considered pressure boundary parts because the body has sufficient wall thickness to withstand design pressure without relying upon the thickness of the seal rings.

Stem

The stem, which connects the actuator and disk, is responsible for positioning the disk. Stems are typically forged and connected to the disk by threaded or welded joints. For valve designs requiring stem packing or sealing to prevent leakage, a fine surface finish of the stem in the area of the seal is necessary. Typically, a stem is not considered a pressure boundary part.

Connection of the disk to the stem can allow some rocking or rotation to ease the positioning of the disk on the seat. Alternately, the stem may be flexible enough to let the disk position itself against the seat. However, constant fluttering or rotation of a flexible or loosely connected disk can destroy the disk or its connection to the stem.

Two types of valve stems are rising stems and nonrising stems. Illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, these two types of stems are easily distinguished by observation. For a rising stem valve, the stem will rise above the actuator as the valve is opened. This occurs because the stem is threaded and mated with the bushing threads of a yoke that is an integral part of, or is mounted to, the bonnet.

There is no upward stem movement from outside the valve for a nonrising stem design. For the nonrising stem design, the valve disk is threaded internally and mates with the stem threads.

|

| Figure 2 - Rising Stems |

|

| Figure 3 -Non-rising Stems |

Valve Actuator

The actuator operates the stem and disk assembly. An actuator may be a manually operated handwheel, manual lever, motor operator, solenoid operator, pneumatic operator, or hydraulic ram. In some designs, the actuator is supported by the bonnet. In other designs, a yoke mounted to the bonnet supports the actuator.

Except for certain hydraulically controlled valves, actuators are outside of the pressure boundary. Yokes, when used, are always outside of the pressure boundary.

Valve Packing

Most valves use some form of packing to prevent leakage from the space between the stem and the bonnet. Packing is commonly a fibrous material (such as flax) or another compound (such as teflon) that forms a seal between the internal parts of a valve and the outside where the stem extends through the body.

Valve packing must be properly compressed to prevent fluid loss and damage to the valve's stem. If a valve's packing is too loose, the valve will leak, which is a safety hazard. If the packing is too tight, it will impair the movement and possibly damage the stem.

Please contact

Thompson Equipment (TECO) with any

valve repair,

valve automation, or new valve requirement. You can visit TECO at

http://www.teco-inc.com or

call 800-528-8997.