|

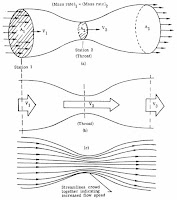

| Water flow measurement device comparison (click for larger view) |

Volumetric water measurement can be broken down into three general operating designs:

- Positive displacement

- Differential pressure

- Velocity

Positive Displacement – Nutating-Disk Flow Meter

Nutating-disk flow meters are the most common meter technology used by water utilities to measure potable-water consumption for service connections up to 3-inch. The nutating-disk flow meter consists of a disk mounted on a spherically shaped head and housed in a measuring chamber. As the fluid flows through the meter passing on either side of the disk, it imparts a rocking or nutating motion to the disk. This motion is then transferred to a shaft mounted perpendicular to the disk. It is this shaft that traces out a circular motion – transferring this action to a register that records flow.There are a variety of differential pressure devices useful for water metering; two of the more common devices include orifice flow meters and venturi flow meters.

Differential Pressure – Orifice Flow Meter

The orifice element is typically a thin, circular metal disk held between two flanges in the fluid stream. The center of the disk is formed with a specific-size and shape hole, depending on the expected fluid flow parameters (e.g., pressure and flow range). As the fluid flows through the orifice, the restriction creates a pressure differential upstream and downstream of the orifice proportional to the fluid flow rate. This differential pressure is measured and a flow rate calculated based on the differential pressure and fluid properties.Differential Pressure – Venturi Flow Meter

The venturi flow meter takes advantage of the velocity-pressure relationship when a section of pipe gently converges to a small-diameter area (called a throat) before diverging back to the full pipe diameter. The benefit of the venturi flow meter over the orifice flow meter lies in the reduced pressure loss experienced by the fluid.The velocity measurement technologies described in this section include the turbine flow meter, vortex-shedding flow meter, and ultrasonic flow meters.

Velocity – Turbine Flow Meter

A multi-blade impellor-like device is located in, and horizontal to, the fluid stream in a turbine flow meter. As the fluid passes through the turbine blades, the impellor rotates at a speed related to the fluid’s velocity. Blade speed can be sensed by a number of techniques including magnetic pick-up, mechanical gears, and photocell. The pulses generated as a result of blade rotation are directly proportional to fluid velocity, and hence flow rate.Velocity – Vortex-Shedding Flow Meter

A vortex-shedding flow meter senses flow disturbances around a stationary body (called a bluff body) positioned in the middle of the fluid stream. As fluid flows around the bluff body, eddies or vortices are created downstream; the frequencies of these vortices are directly proportional to the fluid velocity.Velocity – Ultrasonic Flow Meters

There are two different types of ultrasonic flow meters, transit-time and Doppler-effect. The two technologies use ultrasonic signals very differently to determine fluid flow and are best applied to different fluid applications. Transit-time ultrasonic flow meters require the use of two signal transducers. Each transducer includes both a transmitter and a receiver function. As fluid moves through the system, the first transducer sends a signal and the second receives it. The process is then reversed. Upstream and downstream time measurements are compared. With flow, sound will travel faster in the direction of flow and slower against the flow. Transit-time flow meters are designed for use with clean fluids, such as water.Doppler-effect ultrasonic flow meters use a single transducer. The transducer has both a transmitter and receiver. The high-frequency signal is sent into the fluid. Doppler-effect flow meters use the principal that sound waves will be returned to a transmitter at an altered frequency if reflectors in the liquid are in motion. This frequency shift is in direct proportion to the velocity of the liquid. The echoed sound is precisely measured by the instrument to calculate the fluid flow rate.

Because the ultrasonic signal must pass through the fluid to a receiving transducer, the fluid must not contain a significant concentration of bubbles or solids. Otherwise the high frequency sound will be attenuated and too weak to traverse the distance to the receiver. Doppler-effect ultrasonic flow meters require that the liquid contain impurities, such as gas bubbles or solids, for the Doppler-effect measurement to work. One of the most attractive aspects of ultrasonic flow meters is they are non-intrusive to the fluid flow. An ultrasonic flow meter can be externally mounted to the pipe and can be used for both temporary and permanent metering.

For more information on any flow application, visit http://www.teco-inc.com or call (504) 833-6381.